Bloomberg Intelligence’s Chief U.S. Economist Carl J. Riccadonna Speaks with Capital Market Laboratories - ‘there is immense slack in the economy.’

Lede

We had a conversation with Bloomberg Intelligence’s Chief U.S.Economist Carl J. Riccadonna.

Highlights and Analysis

Carl is a remarkably good communicator and in that vein the transcription acts as a sort of “highlights section” in and of itself.

But here is a narrower highlight reel:

When discussing the impact of COVID and the state of the labor market, we got this (our emphasis added):

With regard to the most critical data to examine in either support of or opposition to the dovish view, Carl noted:

We then discussed the remarkable rebound in GDP and how hawks feel that is a sign of a non-temporary inflation risk, Carl noted:

Please enjoy the transcription of our one-on-one conversation with Bloomberg Intelligence’s chief U.S. economist Carl J. Riccadonna.

One-on-One with Bloomberg Intelligence’s Chief U.S. Economist

Ophir Gottlieb:

First of all, thank you for the report. It was very helpful to understand your take on things. So, I’ll start from the top.

I think your overarching view, even though there are obviously many pieces to it, is that your analysis leads you to believe that even as early as now, there are signs of relief to recent inflation that are emerging. Can you just talk about what those signs of relief are?

Carl J. Riccadonna:

Absolutely. So let me take one step back before we get into those signs of relief, and that was kind of the underlying thesis, which we then looked for corroborating evidence to support.

So, the underlying thesis is basically that the US economy, and most industrialized economies, have not been able to generate significant inflation for the better part of about 30 years. And so this was especially prevalent before the COVID-19 crisis, and the recession happened where we were running the economy extremely lean and still not seeing evidence of inflation pressures building, or wage inflation pressures building in the economy.

The fundamental question that I’m asking myself, as I think about the inflation landscape, is has the tiger changed its stripes, so to speak, as we think about what changed during the COVID crisis?

And certainly, there are some changes, in terms of use of technology, and working from home, and maybe the way we think about work-life balance, and safety protocols, et cetera, et cetera.

There were changes in the economy, some which we’re still only learning of now, but fundamentally, that inability for the economy to generate inflation that has not changed materially over this crisis.

Because when we look at what’s driving the lack of inflation generation in the economy, it really boils down to the largest single input cost in every industry, or almost every industry, and that is the cost of labor.

Without workers having significant bargaining power, then you don’t have much inflation potential in the economy on a sustained basis. Because if I’m a worker on a fixed trajectory of income, if the prices of goods go up in certain categories, then I either substitute or spend less on other categories.

In other words, unless I’m experiencing wage inflation, then I can’t really sustain consumer price inflation. And as we look at the fundamental drivers of that trend over kind of the last 30 years, it’s really three factors.

One, in no particular order, one is the decline in unionization rate. If workers are in a union, they have some bargaining power, some ability to index related to inflation. If they don’t, if they’re not in a union, then they can maybe quit their job and go somewhere else, but the collective bargaining counts for a lot, in terms of worker income trends. And that’s not to say be pro or anti-union, but that’s just the fact of the reality.

The other two factors are globalization and automation. When workers become too expensive, often they’re replaced with technology, or their jobs are shipped overseas to lower labor costs locales, often Asia or Latin America, and so globalization poses a threat as well.

We have a little bit of a trade war going on with China, but we’re still importing huge amounts of goods from China. We have record-wide trade deficits, so the globalization story isn’t really changing, even though we have tariffs in place.

And so, my view is that there are certainly some growing pains as we come out of the very deep recession that we witnessed last year, but I don’t think that the dynamics that have weighed on worker wages, and in turn consumer inflation, over the last 30 years have really changed so much in 2021, or going forward.

OG:

Interesting too, to think back, you said the last 30 or 40 years where we’ve essentially had almost an inability to have inflation.

We actually don’t even have to go that far back.

I’m sure you recall getting out of the Great Recession, there was some pretty fantastical moves by the Federal Reserve, and the hawks were screaming bloody murder.

CJR:

And here we are again, and the same thing is happening, right? So coming out of the Great Recession in ’09, the Fed was embarking on quantitative easing, the Inflationistas and the hawks were saying, “This is going to cost such instability and create hyperinflation in the US economy,” that never came to pass.

Here we are once again, the Fed engaging in quantitative easing, aggressively supporting the economy, and, again, the hawks are squawking and very concerned that we’re going to have a debilitating increase in inflation pressures.

We’re certainly seeing more inflation now than we saw coming out of the Great Recession, but I wouldn’t credit that to the Fed actions necessarily, as much as the fiscal policy that we adopted during the COVID downturn, which really supported household incomes and kind of bridged the gap a lot better than the experience in 2009.

OG:

I would say, no matter how bad the recession was in 2009, it wasn’t actually shutting down our economy and then restarting it.

CJR:

Exactly. It was a much different environment, although on the other side of the coin, we can say that was actually a financial crisis as well.

So, with a deep recession and a financial crisis, which therefore weighed on the economic recovery, this time around we didn’t have a financial crisis to go with the deep recession, but the recession was much deeper, in context.

To kind of think of it in similar terms, one fundamental way of looking at the labor dislocation, the number of people unemployed, and where we stand presently in the economy…

We think that the darkest days of COVID are far, far behind us, but in terms of what I’ll call the jobs deficit, or the level of employment compared to February of 2020, the jobs deficit right now is not very different from where it was at the darkest moment of the 2008, 2009 recession.

OG:

Interesting.

CJR:

This tells us that there is immense slack in the economy. While workers may have some bargaining power as there are skill shortages and mismatches, and we’re trying to restart the economy and there’s some scramble for labor supply, especially skilled labor, I don’t think that will be sustainable, because there is that slack out there.

OG:

Okay. I’m going to play devil’s advocate a little bit. We can look at elements of the CPI increase, like auto prices, for example. There’s others, and they feel… forgive the phrasing, sort of obviously temporary.

Like used auto prices won’t be here forever, but there is this sort of dark cloud hanging over hawks that point to the mistakes in the seventies, where constant adjustments to what was considered sort of CPI relevant, just to create a phrase, led to a late Fed, and ultimately inflation.What do we say to that? Is it still the labor slack argument or is there something else?

CJR:

I think, ultimately, as we’re thinking about inflation, we’re thinking about consumer prices. And so, consumer prices will be dictated by consumer incomes or worker incomes.

The inflation we saw in the 1970s was in part due to Federal Reserve policy that was too accommodative for the better part of about two decades, in fact, and so they nurtured inflation for two decades. We had two oil crises over that period, we totally changed the way foreign currencies operated, moving away from Bretton Woods to totally floating exchange rates in the early 1970s.

There were lots of shock to the system that helped to contribute to a mistake the Fed was making by keeping policy too accommodative over that period as well.

That was two decades. What we’re looking at now is the economy still hasn’t been returned to full employment, and instead it’s already starting to talk about tapering and it’s exit strategy and whatnot, so to draw the parallels between Jerome Powell and the mistakes made over almost a two-decade horizon in the late sixties and the seventies is a little bit of an overdramatization, which is why I refer to that camp as the Inflationista.

OG:

You shared a great chart focusing on how CPI services is a better gauge of economic slack than CPI goods, and you noted that while goods inflation is the highest since 1991, in fact services are merely aligned with their average from the prior economic cycle.

CJR:

Right.

OG:

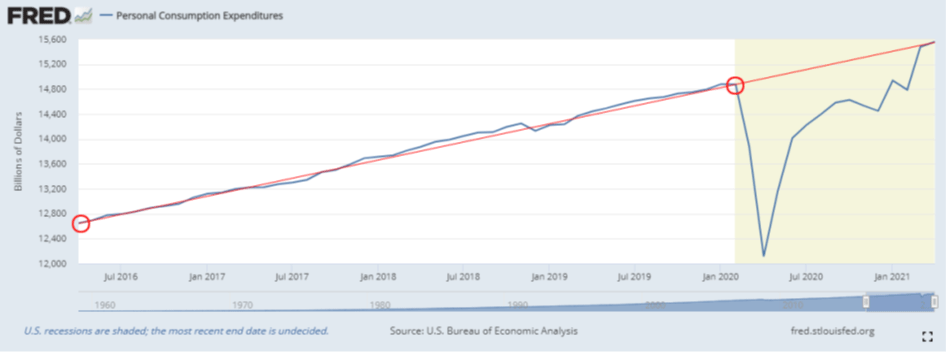

I looked at PCE and I actually did the same thing. I looked at a five-year trend. By trend, I mean I looked at the level of PCE exactly five years ago, drew a circle. I looked at the last reading prior to COVID, drew a circle, and then I just drew a straight line through it.

It turns out that straight line, I couldn’t have made it up if I meant to, is exactly where PCE has risen to today.

So, while the chart looks like it has histrionics, certainly there was a COVID recession, PCE is also merely aligned with the long-term trend.

Help investors understand this difference between the difference in importance between CPI services and CPI goods, and why that’s what you’re focusing on rather than the 1991 highs.

CJR:

Absolutely. CPI services is really a reflection of economic conditions in the domestic economy. What are we paying for medical care, what are we paying for rent, what are we paying for all the types of services that we consume in the economy, whether it’s going to the movies or a restaurant meal, or things of that nature.

CPI goods is largely a reflection of what’s happening overseas, where most of the goods we consume are produced, whether you go to the grocery store or Walmart or shop on Amazon, take a look at the tags, see where those things are produced. More often than not, they’re produced outside of the United States.

So, if I’m concerned about the price change in a good maybe I’m buying on Amazon, it’s really telling me about the economic conditions in the home country where that was manufactured. If I’m looking at goods, it’s either telling me about external economic conditions, commodity prices, or maybe fluctuations in the currency.

If we have a period where the dollar has been weakening, then you tend to be importing inflation pressures from overseas. Now that’s not telling you about the health or the amount of slack in the domestic economy, and so what that certainly is not just looking at the services sector.

They remove food and energy, of course, to reduce volatility, but when they’re looking at the picture, they don’t just take the number at face value. They look at what’s driving the inflation, and if the inflation is really the result of some commodity price pressures or import prices, that is much less concerning to them, that we’re heading into an inflationary environment, than if they saw, for example, that there was a lot of domestic pressure on services, which would tell us if the domestic labor market was heating up as well, when we were getting wage pressures.

That wage pressure inflation, or the wage price spiral, that’s what we saw in the 1970s. We are not seeing that at this moment in the US economy.

OG:

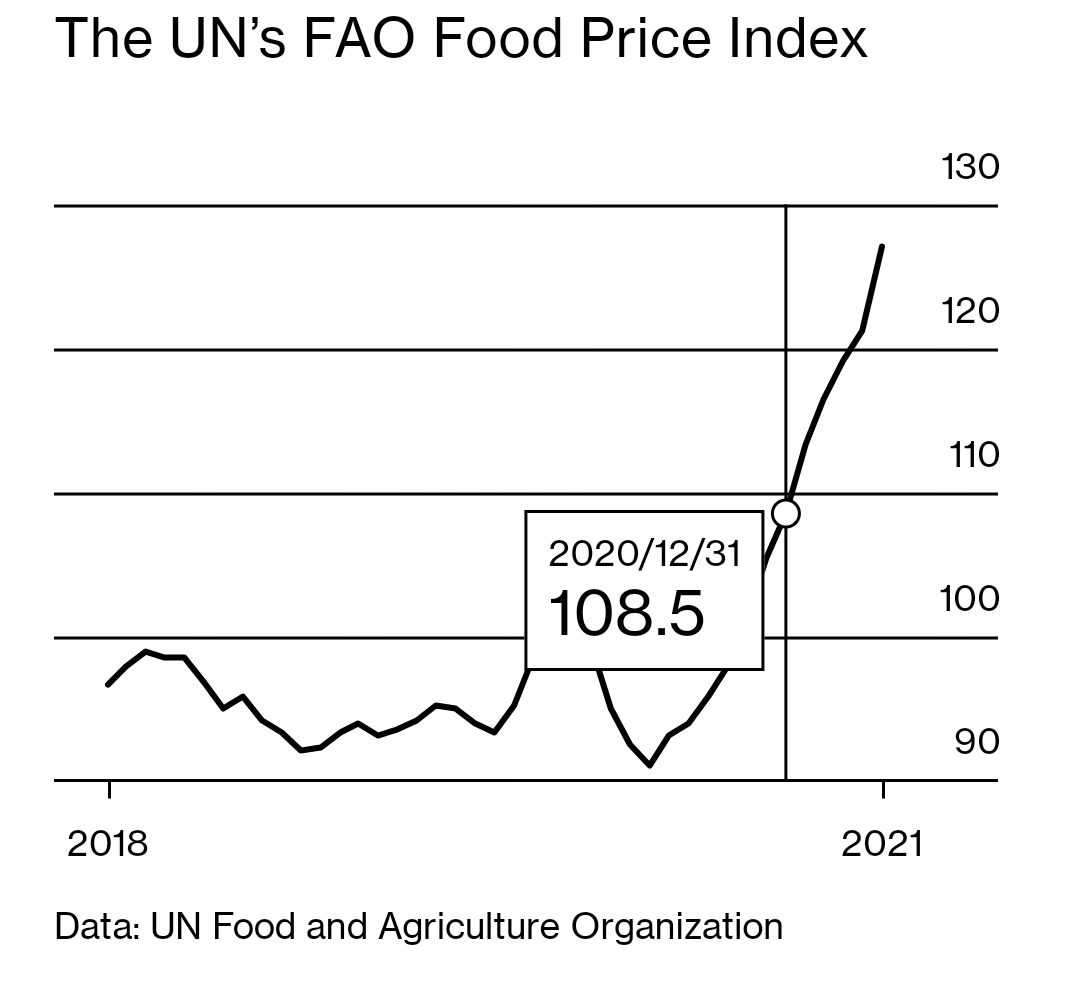

Let me touch on one more thing which is a little bit outside the US, then I’ll come back to national. The UN’s FAO food price index has essentially exploded, and we know from international events that this can cause civil unrest, and et cetera, et cetera.

Is there any worry we should have about what’s going on in that food price index?

CJR:

I don’t know that, for instance, food price inflation causes instability in developed economies, especially old industrialized economies.

There can be some complaining about it, but we tend to have stable enough economic systems with economic stabilizers, whether it’s food stamps or other types of transfer payments, that it doesn’t tend to be destabilizing in the industrialized world.

However, periods of rampant food price inflation, especially if combined with high unemployment or economic slack, have certainly been correlated with periods of instability, whether it’s the Arab spring or other major social, economic, and political movements.

So, absolutely a weak global economy that still has a lot of slack in the system and rising food prices are certainly a recipe, historically, for potential instability. So that’s something absolutely we should be concerned about…

While COVID may seem like a distant memory for a lot of people in developed economies, you could look no further than Brazil or Indonesia, India, and still the crisis is very real and the casualty numbers are much higher, in fact, in 2021 compared to 2020.

I never answered your first question, which was the points we were looking at when we were starting to see the turn, and so, in fact, as we start to look through the CPI and whatnot, you take out these special factors like, okay, the price of going to a music concert or a public event is much higher this year compared to last year. Well, that’s not surprising to anyone, right? You couldn’t sell a concert ticket if you tried, in April 2020.

You’d take out concert tickets and car rentals and airfares and motels, all of the obvious reopening categories, you still have rising inflation pressures, but you have a much softer profile compared to that period.

In fact, as we start to look through, you’re starting to see some signs of things rolling over. Grocery prices have been decelerating.

And as you start to look into some other categories, the hot commodity price categories have started to cool down.

So, whether we’re talking about two by four lumber prices rolling over, a lot of agricultural commodities have started to a roll over as well.

Already things that were very hot in the first quarter of this year in anticipation of the economic reopening, are starting to simmer down.

There’s an old adage in the commodity markets that the cure for high prices is high prices, seems to be playing out before our very eyes, because high prices lead to hoarding and oversupply. And ultimately that leads to a downdraft in prices. And that’s exactly what we’re seeing at this moment.

OG:

Yeah. I think we can add maybe the beginning stages of copper to that as well.

CJR:

Yeah. Copper is another one.

If you look at that different, and I’m not a chemist, but as we look at the ethylenes and those types of petroleum derivatives that go into plastics and different types of consumer products. Petroleum not used for fuel, basically.

You can see, that covers a lot of the things we consume, right? When you think from polyester to floor cleaner, et cetera. All those categories are starting to cool down as well. So, if you look way up the supply chain, you’re starting to see some signs of a potential release percolating through the system.

OG:

As you sit from your perch, what data would move you to consider that inflation may be more persistent than you believe right now? Maybe a better way to ask is, investors are out there reading gobs and gobs of headlines, trying to digest information and data, which may or may not be relevant.

What should investors focus on to manage a belief system that there is a transitory nature to this inflation and what data would pop up and you say, oh, maybe not. Obviously labor costs are one.

CJR:

I would say that the biggest factor without a doubt is going to be labor costs, because if labor inflation is not picking up, if wages are not starting to accelerate, it’s going to be very difficult to sustain those price increases.

Then you tend to see just a one-time increase in price, and then either… Maybe they don’t come back down, but they plateau at a level for an extended period of time, which may be where we’re heading in the housing market incidentally.

Really the crux of the argument is based on various measures of labor market income, whether it’s salary trends or average annual earnings, that’d be employment cost index. All of those labor gauges, I’d have to see continuing to accelerate and not showing signs of rolling over into the back half of this year. And I think that’s going to be a big challenge because really at the moment, we’re hitting peak growth.

And so, the economy is going to grow about 10% in Q2, it slows to 7% next quarter, 5% the quarter after that, then three and a half then three. And these aren’t on my own forecast, these are the consensus forecast among economists. This broad-based view of slowing growth.

Of course, the U S economy is not built to grow at a 10% pace. It’s built to grow around basically 2%. If you take something that’s meant to grow at 2% and ramp it up to 10%, of course there’s going to be frictions and price pressures and distortions in the economy, but we’re at peak right now.

We’re just cresting the hill and we’re going to see slower and slower growth, still well above trend and very healthy economic growth. Make no mistake about it, but the pressures are going to ease and ease, with the foreseeable forecast horizon to let’s say a two-to-three-year time horizon.

If we’re moderating in that trend, then you know if overall growth is slowing, those inflation pressures are going to ease up as well.

So, to answer your question in two summary points, one will be, watching the whole body of labor market indicators to see that there’s no relief in sight. If they’re accelerating, then labor inflation will create that wage price spiral that did develop in the 1970s.

The other part that we’re watching, or the other major gauge is just looking at overall macro-economic activity. And if the pace is continually slowing and slowing and slowing, that’s easing the pressures, the speed limit effect so to speak, on inflation pressures. So that tells you a moderation will be coming well.

OG:

Okay. My last question for you is, it’s the great fear because of this cognitive dissonance that we have of the last recession, and that has to be housing.

Obviously, the last recession was founded in housing prices. It was rather complex due to impropriety, but that’s where the alarm bells were.

We have residential construction costs rising by double digits, buoyed by lumber costs. Again, lumber costs are fading rather substantially. Still high, but fading.

We do have all time historic, low interest rates; the cost of money is less.

We have these, what feels like maybe longer-term trends and dislocations. So, from major cities in the U.S. to other less expensive cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, things like that.

Bloomberg Business Week just put out a piece that read stricter lending standards have reduced the risk in this market compared to the great financial crisis.

Does housing ring alarm bells for you at all? Is there anything in that category of data that we should be watching out for?

CJR:

When we’re in an environment that there are more realtors than homes for sale, that tells you that there are some supply imbalances in the system.

If we look at the inventory levels, we can see that there is just an acute shortage of homes for sale. Then the natural market economics response there is, either supply is going to increase dramatically, or prices are going to be increased dramatically, or some combination of both, to level things out. And, there’s not an immediate shift in the market to make that adjustment.

And that’s what we’re seeing now is the economy is reopening and just at the onset of our discussion, I highlighted some things haven’t changed in the economy, like the lack of worker bargaining power, but some things have. And that’s remote work.

I never would have guessed that I could work from home for a year and maintain a decent level of productivity with the video conferencing and the remote access to my desktop in the office and all these sorts of things. And I’m not the only one.

A lot of people have realized that that potential. And so that has fundamentally changed the real estate market.

There are lasting consequences from the COVID crisis. Some of it is scarring, if people were maybe hurt economically and will never fully get back onto their feet. But some of these are just shifts and evolution in the economy, like an ability to work further from your office, maybe on a permanent basis or a flex scheduling or whatnot.

That has really been a game changer for the real estate market, where people are finding they can live much further from city center than what they previously thought possible.

This is creating the tremendous changes in terms of how we think about urban centers and second tier cities and even more remote locations, assuming they have adequate infrastructure like broadband internet and whatnot there, to support that kind of activity.

I fully agree with the assessment that the regulations put in place after the housing crisis in ’07, ’08, ’09 have made banks much more resilient to the types of shock [experienced in the Great Recession].

Fed bank stress tests, for instance, something we’ll be focusing on later this week, have really changed the risk profile for the housing market, which is so fundamental to the US economy.

We can talk about different corners of the financial market and the amount of exposure there. Many people who own a home or access home equity lines of credit or even through the rental market are impacted.

Real estate and the financial risks around real estate is something that is a multifaceted animal in the economy, and it can be a multifaceted risk or an asset in terms of the supporting economic activity.

What we’re seeing now is an imbalanced market. And ultimately, I sound like a broken record here, as I focus on household incomes as the driver of inflation, also as a driver of the housing market, right? It’s affordability that matters.

You touched on the level of interest rates drives affordability. The price level, house prices in this case, is the other variable in the equation. And it’s not just the cost of buying the home but then matching that carrying cost to household income. So, the income, interest rates, and house prices.

And as we look at interest rates, is the Fed’s in the process of ultimately backing away from all of this accommodation, that’s going to mean higher mortgage rates. And they’ve drifted a little bit in that direction, recently.

Home prices are high, so that’s hurt affordability. And so, the more lagging variable will be what happens to household income.

Will we see such an increase in income that it can withstand that affordability? Well, then, the housing market can continue along, great guns.

If that’s not the case, and there’s a little bit of a soft patch in household income, as we still have basically 6% unemployment in this country and more than 7 million unemployed compared to where we were in February of 2020, well, in that case, then that means affordability is being crimped by the latest developments.

And that should create some downdrafts in the housing sector, ultimately. But housing takes a long time to build a house. So, for the market to find the new stability point will take a little bit of time.

OG:

Is there anything else that I should have asked that you think that I didn’t or something else that you wanted to point out, too?

CJR:

The last point I’ll make, since we’ve been talking about inflation, is inflation expectations.

People are very focused on what’s happening in the TIPS [Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities] market and in surveys.

For instance, the University of Michigan consumer sentiment index has inflation expectations. And so, we saw, along with the acceleration of price pressures that we saw this year, we also saw inflation expectation prep pick up.

And not to debunk them or to downplay their significance, right, because ultimately what will drive inflation is the expectations around inflation.

Jay Powell has said this on a number of occasions, and, really, this is central to the line of thinking at the Fed. If the public thinks price pressures are rising, then it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

However, we have to be careful not to over-interpret what’s happening in the recent moves, because inflation expectations are immensely sensitive to specific categories.

Now, if I asked you the price of some random item in your grocery cart, you probably would miss to a significant degree. But the average American, if you ask them the price of a gallon of gasoline, they know it to the penny, right?

This big rise in inflation expectations that we saw in the first half of the year, that was inflaming the inflationista camp, was very much tied to this dramatic acceleration in retail gasoline prices that we saw as part of the reopening, the Colonial pipeline disruption, some very special factors driving gasoline prices.

Now the gas prices seem to be cresting for the year. And that’s a dangerous thing to say ahead of hurricane season. But, aside from some exogenous shock, it does look like we’re starting to crest in terms of oil prices, gasoline prices. You should see inflation expectations start to moderate as well.

OG:

I feel like this entire economy is an exogenous event, but, yes, I know what you mean. All right.

Thank you so much.

CJR:

Fantastic. Thanks, Ophir.

Conclusion

Long-term investing is far harder than swing trading or day trading.

While some will say that long-term investing is easy, they quickly realize that the long run is just a collection of short runs we all have to endure, and the long term is more difficult to endure than most people imagine.

This is why the long-term is more lucrative than many people assume.

As Morgan Housel has said, rather than assuming long-term thinkers don’t have to deal with nonsense, the question becomes how can you endure a never-ending parade of nonsense.

It’s with this in mind that we have created CML Pro.

Long-term stock research with an auditor verified track record performance.

Learn more about CML Pro: Find the stocks of tomorrow, today, and change your life forever.

Thanks for reading, friends.

Legal

The information contained on this site is provided for general informational purposes, as a convenience to the readers. The materials are not a substitute for obtaining professional advice from a qualified person, firm or corporation. Consult the appropriate professional advisor for more complete and current information. Capital Market Laboratories (“The Company”) does not engage in rendering any legal or professional services by placing these general informational materials on this website.

The Company specifically disclaims any liability, whether based in contract, tort, strict liability or otherwise, for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or special damages arising out of or in any way connected with access to or use of the site, even if I have been advised of the possibility of such damages, including liability in connection with mistakes or omissions in, or delays in transmission of, information to or from the user, interruptions in telecommunications connections to the site or viruses.

The Company makes no representations or warranties about the accuracy or completeness of the information contained on this website. Any links provided to other server sites are offered as a matter of convenience and in no way are meant to imply that The Company endorses, sponsors, promotes or is affiliated with the owners of or participants in those sites, or endorse any information contained on those sites, unless expressly stated.